Understanding Obesity: A Comprehensive Overview

Obesity is a condition where there is an abnormal growth of body fat. This can happen in two main ways: either the fat cells get bigger, which is known as hypertrophic obesity, or the number of fat cells increases, which is called hyperplastic obesity. Sometimes, both can happen at the same time. Obesity is often measured using the Body Mass Index (BMI), a simple calculation based on a person’s height and weight.

It’s important to note that being overweight is usually due to obesity, but there are other reasons why someone might be heavier. For example, abnormal muscle development or fluid retention can also cause an increase in body weight.

However, not all obese individuals have the same health risks. How fat is distributed in the body affects health risks. When people store more fat around their abdomen, it is known as android obesity or “apple-shaped” fat distribution. This type of fat distribution increases the risk of health problems like heart disease and diabetes. On the other hand, people with a more even fat distribution around their body have gynoid obesity or “pear-shaped” fat distribution, which is generally considered less risky for health.

How Common Is Obesity?

Obesity is now one of the most common forms of malnutrition globally, affecting people in both developed and developing countries. It impacts not just adults but children too. In many parts of the world, obesity is becoming more of a public health concern than undernutrition.

In industrialized countries, the rise in obesity rates is mainly due to lower levels of physical activity rather than changes in diet or other factors. However, measuring the exact prevalence of obesity can be challenging. Different countries have different ways of defining and measuring obesity, making direct comparisons difficult. Despite these challenges, it’s estimated that 20 to 40 percent of adults and 10 to 20 percent of children and adolescents in developed countries are affected by obesity.

Understanding obesity and its implications is crucial for tackling this growing health issue. By knowing more about how fat is stored in the body and the risks associated with different types of obesity, we can better manage and reduce the health impacts of this condition.

Obesity is a major risk factor for many long-term health problems, which is important to remember when planning for public health. When obesity rates go up in a population, we often see a pattern in how these health problems develop over time.

First, people may start to experience high blood pressure (hypertension), high cholesterol (hyperlipidemia), and issues with blood sugar (glucose intolerance). These are usually the first signs that obesity is affecting people’s health. Over the years, more serious conditions like heart disease and complications from diabetes, such as kidney failure, can develop.

Unfortunately, it seems that developing countries might soon face the same high rates of these diseases that industrialized countries experienced about 30 years ago. This makes it even more important to focus on preventing obesity and its related health issues.

Epidemiological Determinants of Excessive Weight Gain

(a) Age:

Excessive weight gain can occur at any age, but the risk generally increases as people get older. Infants who gain a lot of weight early on have a higher chance of becoming overweight later in life. About one-third of adults who are overweight have been so since they were children. It’s known that most fat cells are formed early in life, and infants who are overweight tend to develop more fat cells, which is known as hyperplastic obesity. This type of obesity is particularly challenging to treat in adults using conventional methods.

(b) Sex:

Generally, women have a higher rate of excessive weight gain compared to men, although men may have higher rates of being overweight. A study from Framingham, USA, found that men tend to gain the most weight between the ages of 29 and 35, while women gain the most weight between the ages of 45 and 49, typically around menopause. It has also been suggested that a woman’s Body Mass Index (BMI) can increase with each pregnancy, with an average increase of about 1 kg per pregnancy. However, in many developing countries, frequent pregnancies with short intervals between them are often associated with weight loss rather than weight gain.

(c) Genetic Factors:

Genetics also play a role in the development of excessive weight gain. Studies on twins have shown that identical twins often have similar body weights, even when raised in different environments. Additionally, the way fat is distributed in the body is largely inherited, with genetics accounting for about 50% of the variation among people. Recent research has indicated that the amount of abdominal fat someone has is also influenced by genetics, accounting for 50-60% of individual differences.

(d) Physical Inactivity:

There is strong evidence that regular physical activity helps protect against unhealthy weight gain. In contrast, a sedentary lifestyle, including sitting for long periods and inactive leisure activities like watching TV, promotes weight gain. Physical activity and fitness are important for reducing the health risks associated with being overweight.

In some cases, a significant drop in physical activity, without a corresponding decrease in food intake, can lead to weight gain. This is often seen in athletes who retire or young people who sustain injuries. A lack of physical activity can lead to weight gain, which in turn can make it harder to stay active, creating a vicious cycle. Reduced energy output is likely a more significant factor in the development of excessive weight gain than previously thought.

(e) Socio-Economic Status:

The relationship between excessive weight gain and social class has been studied extensively. There is a clear inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and excessive weight gain. However, in some wealthy countries, being overweight is more common among lower socio-economic groups.

(f) Eating Habits:

Eating habits, such as snacking between meals or preferring sweets, refined foods, and fats, are usually established early in life. The type of diet, how often people eat, and the amount of energy they get from their food all play a role in the development of excessive weight gain. A diet that provides more energy than the body needs can lead to prolonged high levels of fats in the blood after eating, which can cause the body to store more fat, leading to weight gain.

Nowadays, television and print media contribute to weight gain by heavily advertising fast food outlets that sell energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, and drinks, often categorized as “eat least” in dietary guidelines. These advertisements influence daily eating habits and consumer demand, which can be affected by advertising, marketing, culture, fashion, and convenience.

It has been estimated that a child who needs 2,000 kcal per day but consumes 100 kcal extra per day could gain about 5 kg in a year. The accumulation of one kilogram of fat corresponds to 7,700 kcal of energy.

(g) Psychosocial Factors:

Emotional issues like depression, anxiety, frustration, and loneliness can contribute to excessive weight gain in both children and adults. People who are significantly overweight often feel withdrawn, self-conscious, and lonely, and they may eat secretly to cope with their emotions. Understanding the circumstances that led to excessive weight gain is crucial for developing the best management plan.

(h) Familial Tendency:

Excessive weight gain often runs in families, meaning that obese parents are more likely to have obese children. However, this isn’t always due to genetics alone; lifestyle and environmental factors also play a significant role.

(i) Endocrine Factors:

Hormonal imbalances can sometimes contribute to excessive weight gain. Conditions like Cushing’s syndrome and growth hormone deficiency are examples where endocrine factors may be involved.

(j) Alcohol:

A recent review of studies found that alcohol consumption generally has a positive relationship with body fat in men, meaning it tends to increase adiposity. However, for women, the relationship between alcohol and body fat is generally negative, meaning alcohol consumption may not have the same effect on increasing body fat as it does in men.

(k) Education:

In many developed societies, there is an inverse relationship between education level and the prevalence of weight gain. This means that people with higher levels of education are generally less likely to be overweight.

(l) Smoking:

It has been known for over a century that smoking can lower body weight. More detailed studies in recent years have shown that, on average, smokers tend to weigh less than those who have quit smoking, with people who have never smoked falling somewhere in between.

(m) Ethnicity:

Certain ethnic groups in industrialized countries seem to be particularly prone to developing obesity and its related health problems. Research suggests that this may be due to a genetic predisposition to weight gain, which becomes more noticeable when these groups adopt a more affluent lifestyle.

(n) Drugs:

Some medications can contribute to weight gain. These include drugs like corticosteroids, contraceptives, insulin, and beta-adrenergic blockers. These medications can promote weight gain as a side effect.

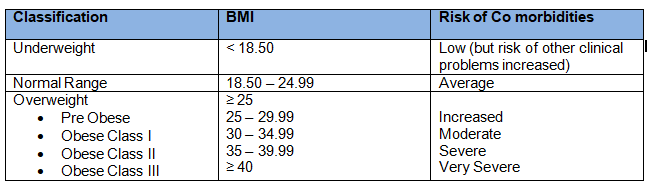

Using BMI to Classify Weight Gain and Obesity

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a simple measure that compares a person’s weight to their height, commonly used to classify underweight, overweight, and obesity in adults. BMI is calculated by dividing an individual’s weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters (kg/m²).

For example, if an adult weighs 70 kg and their height is 1.75 meters, their BMI would be calculated as follows:

BMI = 70 (kg) / 1.75² (m²) = 22.9

BMI classifications help identify whether a person is underweight, has a healthy weight, is overweight, or falls into different categories of obesity. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity is classified as having a BMI of 30.0 or higher. This classification is based on the relationship between BMI and the risk of mortality.

The WHO guidelines also include an additional subdivision for those with a BMI between 35.0 and 39.9. This is because the management strategies for individuals with higher BMI levels may differ significantly, recognizing the increased health risks and the need for different treatment approaches for severe obesity.

By using BMI, healthcare professionals can more easily assess and address the health risks associated with weight gain and obesity.

Understanding Obesity and BMI

BMI (Body Mass Index) values are consistent for both men and women, regardless of age. The BMI chart shows a simple link between BMI and the risk of developing other health issues, known as comorbidities. However, this relationship can be influenced by factors like diet, ethnicity, and physical activity levels. The risk of health problems increases continuously and gradually with a BMI above 25.

While a BMI of 30 or higher generally indicates an excess of body fat, BMI alone does not differentiate between weight from muscle and weight from fat. Because of this, the link between BMI and body fat can vary based on body structure and proportions. For example, Polynesians often have a lower percentage of body fat than Caucasian Australians with the same BMI. Also, the percentage of body fat tends to increase with age, up to 60-65 years and is typically higher in women than in men with the same BMI. Therefore, when using BMI to estimate body fat, it’s important to interpret the values carefully, especially when comparing different groups.

Central Fat Accumulation and Health Risks

Fat stored in the abdominal area, known as intra-abdominal or central fat, has several unique characteristics compared to fat stored under the skin (subcutaneous fat). Central fat contains more cells per unit mass, has a higher blood flow, and more receptors for hormones like cortisol and testosterone. It also responds more strongly to signals that break down fat (lipolysis). Because of these differences, central fat is more prone to changes in how it stores and processes fat.

Additionally, intra-abdominal fat cells are located near the liver, which increases the flow of fatty acids to the liver. This can lead to an increased risk of developing insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome—a group of conditions that include high insulin levels, abnormal blood fats, glucose intolerance, and high blood pressure. These conditions are often linked with central fat accumulation and can increase the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).

Before menopause, women tend to have more lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme involved in fat storage, and higher LPL activity in the gluteal (buttock) and femoral (thigh) areas. These areas contain larger fat cells than those found in men. However, these differences typically disappear after menopause.

Overall, understanding how fat is distributed in the body and its impact on health is crucial for managing weight and reducing the risk of related health problems.

Assessing Obesity

Before we dive into assessing obesity, it’s helpful to understand the different components that make up our body:

- Active Mass: This includes muscles, liver, heart, and other organs that are actively involved in the body’s metabolic processes.

- Fatty Mass: This is the fat stored in the body, which is the main focus when assessing obesity.

- Extracellular Fluid: This includes all the fluids outside cells, such as blood and lymph.

- Connective Tissue: This comprises skin, bones, and other connective tissues that provide structure and support to the body.

Structurally, obesity is characterized by an increase in fatty mass at the expense of other body components. Notably, the water content in the body does not increase in cases of obesity.

While obesity can often be identified visually, a precise assessment requires specific measurements and reference standards. The most commonly used criteria for assessing obesity include:

Body Weight

Although body weight alone is not an exact measure of excess fat, it is a widely used indicator. In many studies, obesity is often defined by body weight measurements that are two standard deviations (+2 SD) above the median weight for a given height. This cut-off point helps identify individuals who are significantly above the average weight for their height, indicating potential obesity.

Body Mass Index (BMI) and Broca Index:

Both BMI and the Broca index are commonly used to assess obesity. A recent FAO/WHO/UNU report provides reference tables for BMI, which can be used internationally to determine obesity prevalence in a community. These standards offer a reliable way to compare data across different populations.

Skinfold Thickness:

A significant portion of body fat is located just under the skin, making skinfold thickness a useful measure for assessing body fat. This method is quick and non-invasive, using calipers like the Harpenden skin calipers to measure fat at four key sites: mid-triceps, biceps, subscapular, and suprailiac regions. The total measurement (i.e. sum of the measurements) should ideally be less than 40 mm in boys and 50 mm in girls. However, there are some limitations to this method. Standards for subcutaneous fat are not well established, and in cases of extreme obesity, taking accurate measurements can be difficult. Additionally, skinfold measurements often suffer from poor repeatability.

Waist Circumference and Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR):

Waist circumference is measured at the midpoint between the lower edge of the rib cage and the iliac crest. This measurement is simple, does not depend on height, and correlates closely with both BMI and WHR. It provides a good approximation of intra-abdominal fat mass and overall body fat. An increased waist circumference is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and other chronic conditions. Men with a waist circumference over 102 cm and women over 88 cm are considered to have a higher risk of metabolic complications. The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is another indicator; a WHR greater than 1.0 in men and 0.85 in women typically suggests abdominal fat accumulation.

Other Methods:

There are three more accurate, albeit complex, methods for estimating body fat. These include measuring total body water, total body potassium, and body density. However, these techniques are complex and not practical for routine clinical use or large-scale epidemiological studies. The development of methods to measure fat cells has also opened new avenues in obesity research.

Overall, these methods provide various ways to assess body fat, each with its advantages and limitations. Using these measurements, healthcare professionals can better understand an individual’s body composition and related health risks.

Hazards of Obesity

Obesity poses significant health risks and negatively impacts overall well-being, leading to both increased morbidity and mortality.

(a) Increased Morbidity

Obesity is a major risk factor for developing several serious health conditions. It increases the likelihood of:

- Hypertension: High blood pressure, which can lead to other heart-related issues.

- Diabetes: Particularly type 2 diabetes, which is linked to high body fat levels.

- Gallbladder Disease: Obesity can lead to the formation of gallstones and other gallbladder problems.

- Coronary Heart Disease: Excess body weight puts extra strain on the heart, increasing the risk of heart disease.

- Certain Types of Cancer: Obesity is associated with a higher risk of hormonally related cancers (like breast and prostate cancer) and large bowel cancers.

In addition to these serious conditions, obesity can cause several other health issues that, while not typically fatal, contribute significantly to discomfort and reduced quality of life. These include:

- Varicose Veins: Swollen and enlarged veins, usually in the legs.

- Abdominal Hernia: A condition where an organ pushes through an opening in the muscle or tissue that holds it in place.

- Osteoarthritis: Joint pain and stiffness, particularly in the knees, hips, and lower back.

- Flat Feet: A condition where the arches of the feet flatten out, causing pain and discomfort.

- Psychological Stress: Particularly during adolescence, obesity can lead to emotional and psychological stress, including issues with self-esteem and social interactions.

Additionally, obese individuals face higher risks during surgery and may experience reduced fertility.

(b) Increased Mortality

Obesity is also linked to higher mortality rates. The Framingham Heart Study in the United States found a significant increase in sudden deaths among men who were more than 20 percent overweight compared to those with normal weight. This increased mortality is mainly due to a higher incidence of hypertension and coronary heart disease among obese individuals. There is also a notable increase in deaths related to kidney diseases. Overall, obesity lowers life expectancy and contributes to premature death.

While much is known about the risks associated with obesity, more research is needed to understand the relationship between different levels of obesity and their specific impacts on morbidity and mortality.

Understanding these hazards emphasizes the importance of maintaining a healthy weight to reduce the risk of these severe health outcomes.

| Greatly Increased | Moderately Increased | Slightly Increased |

| 1. NIDDM 2. Gall Bladder Disease 3. Dyslipidaemia 4. Insulin Resistance 5. Breathlessness 6. Sleep Apnea | 1. CHD (Coronary Heart Disease) 2. Hypertension 3. Osteoarthritis (Knees) 4. Hyperuricaemia and gout | 1. Cancer (breast cancer in postmenopausal women, endometrial cancer and colon cancer) 2. Reproductive hormone abnormalities 3. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome 4. Impaired Fertility 5. Low back pain 6. Increased Risk of Anaesthesia Complications 7. Fetal Defects associated with maternal obesity. |

Prevention and Control of Obesity

Weight control is generally defined as the strategies used to keep body weight within the “healthy” range of Body Mass Index (BMI), which is between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m² for adults, according to the WHO Expert Committee (1995). Effective weight control includes preventing any weight gain of more than 5 kg in all individuals. For those who are already overweight, the initial goal should be to reduce body weight by 5-10 percent.

Preventing obesity should start in early childhood, as it is much easier to manage in children than in adults. The primary focus of controlling obesity is on weight reduction, which can be achieved through a combination of dietary changes and increased physical activity.

(a) Dietary Changes

The following dietary principles are key to both preventing and treating obesity:

- Reduce Energy-Dense Foods: Lower the intake of foods high in simple carbohydrates and fats, which are high in calories but low in nutrients.

- Increase Fiber Intake: Include more fiber in the diet by consuming unrefined foods, which can help with satiety and reduce overall calorie intake.

- Ensure Adequate Nutrition: Even with low-energy diets, it is important to ensure that all essential nutrients are included. Most weight reduction diets are based on a 1000 kcal daily model for adults.

- Align with Existing Nutritional Patterns: Diets should be similar to the individual’s regular eating patterns to increase the likelihood of adherence.

The most fundamental aspect of dietary control is ensuring that calorie intake does not exceed what is necessary for the body’s energy expenditure. This often requires behavioral changes and strong motivation to lose weight and maintain a healthy weight. Unfortunately, most attempts to achieve significant weight loss through dietary advice alone tend to be unsuccessful.

(b) Increased Physical Activity

Regular physical activity is a crucial component of any weight reduction program. Exercise helps increase energy expenditure, which is vital for weight loss and long-term weight management. Engaging in consistent, regular physical exercise can significantly aid in burning calories and maintaining a healthy body weight.

(c) Other Methods

- Appetite Suppressing Drugs: These have been tried as a method to control obesity but are generally not effective in producing substantial weight loss in severely obese patients.

- Surgical Treatments: Surgical options, such as gastric bypass, gastroplasty, and jaw wiring, have been explored to restrict food intake. However, these methods have had limited success and are usually considered only in extreme cases.

In summary, one should not expect rapid or guaranteed results from obesity prevention programs. Health education plays a crucial role in teaching people how to reduce excess weight and prevent obesity. A promising approach is to identify children who are at risk of becoming obese and develop strategies to prevent it. Early intervention and education are key components in effectively managing and preventing obesity.