What is Diabetes?

Diabetes is no longer seen as a single disease — it’s a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) due to problems in insulin production or action. Insulin is a hormone that controls how our body uses sugar, fat, and proteins for energy.

When insulin doesn’t work properly or isn’t produced enough, glucose builds up in your blood, leading to both short- and long-term complications affecting the heart, kidneys, eyes, nerves, and immune system.

Types of Diabetes Mellitus

Definition and Diagnostic Criteria

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. The diagnosis is based on standardized blood glucose and HbA1c thresholds established by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

| Test | Diagnostic Cut-off for Diabetes | Prediabetic/Borderline range |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) | ≥ 126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/L) | 100-125 mg/dl (5.6 – 6.9 mmol/L) |

| 2-Hour Plasma Glucose (OGTT) | ≥ 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/L) after 75 g glucose load | 140-199 mg/dl (7.8 – 11.0 mmol/L) |

| HbA1c (Glycated Hemoglobin) | ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) | 5.7% – 6.4% |

| Random Plasma Glucose | ≥ 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/L) with classical symptoms (polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss) | – |

Type 1 Diabetes (Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus)

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease characterized by selective destruction of the insulin-producing β-cells in the pancreatic islets. Autoreactive T-cells and autoantibodies such as anti-GAD65, IA-2, and ZnT8 mediate it. It is associated with HLA-DR3, DR4, and DQ8 alleles. Viral infections (e.g., Coxsackie B, enteroviruses) and early environmental triggers may precipitate β-cell autoimmunity in genetically predisposed individuals. The progressive loss of β-cells results in absolute insulin deficiency, leading to complete dependence on exogenous insulin for survival (PMC, 2010).

Epidemiology:

T1DM accounts for 5–10 % of all diabetes cases globally. The global prevalence is rising by 3–4 % per year, especially in children under 15 years. In 2021, an estimated 8.4 million people worldwide lived with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), with over 500,000 new diagnoses annually (PubMed, 2022). Incidence is highest in Northern Europe (15–30 per 100,000 children per year) and lowest in Asia and South America (DMS Journal, 2025).

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

T2DM develops through a combination of insulin resistance in muscle, liver, and adipose tissue, and progressive β-cell dysfunction. In early disease, β-cells compensate by hypersecreting insulin. Over time, glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, and inflammation cause β-cell exhaustion. Obesity and ectopic fat deposition impair insulin signaling pathways (IRS-1/PI3K/AKT), reducing glucose uptake and increasing hepatic glucose output (Diabetes Care, 2024).

Epidemiology:

T2DM constitutes 90–95 % of all diabetes cases worldwide. According to the IDF Diabetes Atlas 2021, approximately 537 million adults (20–79 years) have diabetes, with the highest growth in South Asia, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa (NCBI, 2023).

Global prevalence is projected to reach 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 if current trends persist

(IDF, 2021).

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

GDM is defined as glucose intolerance first recognized during pregnancy. During mid- to late pregnancy, placental hormones (human placental lactogen, cortisol, progesterone, growth hormone) create a physiologic insulin-resistant state. In women with limited β-cell reserve, this compensation fails, leading to hyperglycemia. The resulting metabolic stress affects both mother and fetus, increasing the risk of macrosomia, preeclampsia, and neonatal hypoglycemia (PubMed, 2020).

Epidemiology:

Globally, 1 in 6 live births (≈ 16–18%) is affected by hyperglycemia in pregnancy, and about 84% of these cases are GDM (IDF Atlas, 2021). Women with prior GDM have a 7–10 times greater risk of developing T2DM later in life (ADA Standards of Care, 2025).

Impaired Glucose Regulation (Prediabetes — IFG / IGT)

It results from mild insulin resistance and early β-cell dysfunction. Persistent postprandial hyperglycemia (impaired glucose tolerance) or elevated fasting glucose (impaired fasting glucose) indicates progressive β-cell decline (Diabetes Care, 2024).

Epidemiology:

Prediabetes affects an estimated 480 million adults worldwide, many of whom remain undiagnosed.

Each year, 5–10 % of individuals with prediabetes progress to overt T2DM. The Diabetes Prevention Program (NEJM, 2002) showed that lifestyle changes—5–7 % weight loss and ≥150 min/week of physical activity—can reduce progression risk by 58 % (NEJM, 2002).

The Global Diabetes Epidemic

Diabetes is now considered an “iceberg disease” — with many undiagnosed cases beneath the surface. Over 150 million people globally are living with diabetes, and this number is expected to double by 2025, especially in India and China.

Industrialization, urbanization, and changing diets are fueling this rise. More alarming is the increasing number of young adults and even teenagers being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

South-East Asia alone is projected to have over 80 million diabetics by 2025, with most cases in urban areas due to sedentary lifestyles and unhealthy diets.

By 2050, International Diabetes Federation projections show that 1 in 8 adults, approximately 853 million, will be living with diabetes, an increase of 46%

Symptoms and Signs of Different Types of Diabetes

Clinical presentation varies by diabetes type. Type 1 often presents abruptly with classic hyperglycaemic symptoms and a substantial risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis. Type 2 usually develops insidiously; many people are asymptomatic for years and are diagnosed after complications develop. Gestational diabetes is most often asymptomatic and detected by screening; prediabetes rarely causes overt symptoms.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)

Type 1 typically presents over days to weeks with the classic triad of polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia; unintended weight loss and profound fatigue are also common. Several pediatric and registry studies report very high frequencies of these symptoms at diagnosis — polyuria and polydipsia are reported in ~90–97% of children at presentation, weight loss in ~40–85% depending on the cohort (PubMed, 2011).

Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis:

A large international review shows wide geographic variation in DKA frequency at diagnosis (from ~13% up to 80%), with many countries reporting DKA in 30–40% of newly diagnosed children and adolescents. Contemporary registry analyses still find DKA at onset in roughly one-third of youth with T1DM in many settings (PMC).

Practical note

Because T1DM often causes clear symptomatic hyperglycemia, most symptomatic patients will report multiple classic symptoms (polyuria/polydipsia/weight loss). However, atypical or mild presentations do occur, especially in adults (LADA) (PubMed, 2011)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

Pattern of onset:

T2DM usually develops slowly; many patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis. Estimates vary by population, but up to about one-half of people with T2DM may have no noticeable symptoms at the time they are diagnosed — detection often follows screening or investigation of complications.

Common symptoms and relative frequencies:

When symptoms occur, they often overlap with those of type 1 but are generally less severe. Reported features include polyuria and polydipsia (frequency rises with degree of hyperglycemia), fatigue, blurred vision, recurrent infections (skin, urinary, fungal), slow wound healing, and sensory symptoms from neuropathy. Large clinical reviews and practice guidelines note that nonspecific symptoms (fatigue, visual disturbance) are common; neuropathic symptoms may already be present at diagnosis in a minority of patients. Quantitatively, neuropathy is present in ~7.5% at diagnosis in some cohorts, rising with disease duration (PMC).

Complications as presenting features

Because T2DM can remain undetected, complications (retinopathy, neuropathy, foot ulcers, cardiovascular disease) sometimes prompt the initial diagnosis. Providers should therefore screen for end-organ damage even at the first identification of hyperglycemia (CDC).

Type 2 diabetes shares many of these symptoms, but they are usually milder and develop more gradually. Consequently, the condition may go undiagnosed for several years, sometimes only being detected after complications appear. This makes it crucial to recognize and monitor risk factors.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

Clinical detection pattern

GDM is most often asymptomatic and detected through routine pregnancy screening (typically at 24–28 weeks). Classic hyperglycaemic symptoms are uncommon because the hyperglycemia is usually milder than in overt diabetes. Screening is recommended because symptoms do not reliably detect GDM.

Maternal and fetal clues (when present)

When hyperglycemia is more pronounced, pregnant people may report polyuria or polydipsia. More commonly, GDM is suspected because of ultrasound findings (e.g., macrosomia) or abnormal screening results rather than maternal symptoms (PMC).

Prediabetes (Impaired fasting glucose / Impaired glucose tolerance)

Symptom profile

Prediabetes (IFG/IGT; HbA1c 5.7–6.4%) is usually asymptomatic. Some people report nonspecific symptoms such as mild fatigue or intermittent blurred vision, but these are neither sensitive nor specific for prediabetes; diagnosis relies on laboratory testing.

Prognostic importance

Although asymptomatic, prediabetes confers an increased risk of progression to T2DM (approximately 5–10% per year in many cohorts) and is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk than normoglycaemia. Early lifestyle intervention is effective in preventing progression.

Key symptom-specific notes with incidence where available

Polyuria/polydipsia/polyphagia

These “three Ps” are near-universal in symptomatic T1DM (≈90–97% in many pediatric cohorts) but are present less consistently in T2DM and prediabetes; their frequency in T2DM depends on hyperglycemia severity (PubMed, 2011).

Unintended weight loss

Common and often pronounced in T1DM; less typical in T2DM (but may occur in prolonged undiagnosed cases). Pediatric series reports weight loss in large fractions of new-onset T1DM patients (up to ~80% in some cohorts) (PubMed, 2011).

Fatigue and malaise

A nonspecific but common complaint across types; frequently reported in both T1DM and T2DM, and sometimes the only symptom prompting testing. Exact prevalence varies with study design and population (PMC)

Blurred vision

A common transient symptom caused by osmotic changes in the lens may occur in both T1DM and T2DM when hyperglycemia is present. Frequency is substantial but variably reported across studies (PMC).

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

A presenting feature in a substantial fraction of T1DM patients at diagnosis (many series report ~30–40% overall; range is wide by country). DKA is uncommon as an initial presentation of uncomplicated T2DM except in specific phenotypes or when stressors exist (PMC, 2012).

Neuropathic symptoms (tingling, numbness, burning)

Distal symmetric polyneuropathy is the most common form of diabetic neuropathy. Estimates place neuropathy prevalence at ~10–15% at diagnosis for some T2DM cohorts and up to ~50% (or higher) among patients with long-standing diabetes; painful neuropathy prevalence is variable (studies report wide ranges, 10–70% depending on population and case definition) (PMC, 2024).

Slow wound healing, recurrent infections, and foot ulcers

Delayed healing and infection are more typical of long-standing or poorly controlled diabetes. The lifetime risk of a diabetic foot ulcer is commonly cited as 15–25%, with an annual incidence of around 1–2% in general diabetic populations (higher in high-risk subgroups) (PMC,2018).

Diabetic retinopathy as a presenting clue

Though retinopathy typically reflects chronic hyperglycemia, it may already be present at diagnosis of T2DM; population studies show overall retinopathy prevalence among people with diabetes ranging from ~20–30% (higher in some cohorts), and sight-threatening disease in a substantial minority (CDC).

Asymptomatic/undiagnosed diabetes

Large population surveys indicate a substantial pool of undiagnosed diabetes; for example, in the U.S., several million adults meet laboratory criteria for diabetes but are unaware. Globally, a considerable proportion of people with T2DM are asymptomatic at diagnosis. This underlines the role of screening in at-risk groups (PMC, 2022).

Why Early Diagnosis of Diabetes Matters

If left undiagnosed or poorly managed, diabetes leads to severe complications:

Diabetic Nephropathy

Diabetic Nephropathy (DN) is a leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) worldwide. Around 30–40% of people with diabetes develop kidney damage during their lifetime, marked by elevated urinary albumin or reduced glomerular filtration rate (NCBI, 2023).

The annual incidence of diabetic nephropathy varies between 2 and 5% per year among diabetics, depending on control and duration of disease (PMC, 2022). In contrast, the risk of ESRD is 6–10 times higher in diabetics compared to non-diabetics — for instance, 158 vs 25 cases per 100,000 person-years in a German cohort (Oxford Academic, 2011).

Diabetic kidney disease contributes to nearly 40–50% of all CKD cases in India, with incidence rising alongside poor glycemic and blood pressure control.

In summary, diabetes increases the likelihood of developing serious kidney disease by five to ten times, making strict control of blood sugar and blood pressure essential for prevention.

Diabetic Retinopathy and Vision Loss

Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) is one of the most common microvascular complications of diabetes and a leading cause of preventable vision loss. Globally, around 22% of people with diabetes have some form of DR, while about 6% develop sight-threatening retinopathy such as proliferative DR or macular edema (Medscape, 2024).

In India, studies report that 30–50% of diabetics show signs of retinopathy, and about 20–25% have vision-threatening forms at first presentation (PubMed, 2021). The risk increases sharply with duration of diabetes, poor glycemic control, and the presence of hypertension or nephropathy.

Long-term follow-up studies found that over 10 years, 1–5% of diabetics become blind and up to 30% develop moderate visual impairment (PubMed, 1994).

In summary, diabetic retinopathy affects roughly one in three diabetics, and 1 in 20 may develop severe vision loss without early detection and control. Regular eye screening and good glucose management remain key to prevention.

Increase the Risk of Heart Attack and Stroke

Diabetes significantly increases the risk of heart attack and stroke, mainly due to accelerated atherosclerosis and vascular damage.

According to the American Heart Association and Heart Foundation, people with diabetes are 2–4 times more likely to suffer from a heart attack or stroke than non-diabetics — the often-quoted “3×” risk is a midpoint of this range (Heart Foundation, 2024).

Large studies show that type 2 diabetes roughly doubles the risk of coronary heart disease, even after adjusting for blood pressure, smoking, and BMI (Circulation, 2004).

For stroke, risk elevation is somewhat lower but still substantial. The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration reported hazard ratios of 2.27 for ischemic stroke and 1.56 for hemorrhagic stroke among diabetics versus non-diabetics (Lancet, 2010).

In summary, diabetes increases the likelihood of both heart attack and stroke by about 2–3 times, depending on duration, control, and comorbidities. Good management of blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol markedly reduces this risk.

Diabetic Neuropathy

Diabetic Neuropathy (DN) is a common complication of long-term diabetes, caused by chronic high blood sugar damaging peripheral nerves. It affects about 50% of people with diabetes over time (NIH, 2023). The most frequent type is peripheral neuropathy, leading to numbness, burning pain, or tingling in the feet and hands.

The risk increases with poor glycemic control, longer duration of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Studies show diabetics are up to 2.5 times more likely to develop peripheral neuropathy than non-diabetics (Diabetes Care, 2020).

Neuropathy contributes to diabetic foot complications, as loss of sensation prevents early detection of injuries or infections. Combined with poor circulation, this can lead to ulcers, gangrene, and amputations. Globally, up to 15% of diabetics develop foot ulcers, and 1–4% require amputation during their lifetime (WHO, 2023).

In summary, diabetic neuropathy affects nearly half of all diabetics, and 1 in 6 may develop a foot ulcer due to nerve and vascular damage. Tight glucose control, daily foot inspection, and proper footwear are vital to prevent severe disability.

Increased Risk of Infections and Delayed Wound Healing in Diabetes

People living with diabetes are significantly more prone to infections and delayed wound healing due to the long-term effects of high blood sugar on the immune and vascular systems.

Persistent hyperglycemia weakens the body’s natural defense mechanisms. High blood glucose impairs white blood cell function, especially neutrophil activity and chemotaxis, making it harder to fight bacteria and fungi (NIH, 2023). Reduced blood circulation in small vessels further limits the delivery of oxygen and immune cells to tissues, creating an environment where infections—such as urinary tract infections, skin infections, pneumonia, and foot ulcers—develop more easily (PubMed, 2020)

Diabetes also slows the wound-healing process. Elevated glucose damages collagen formation, delays angiogenesis (growth of new blood vessels), and reduces fibroblast activity, which are essential for tissue repair (PubMed, 2022). Poor sensation due to neuropathy means that minor injuries, particularly on the feet, often go unnoticed and become chronic ulcers.

Studies show that people with diabetes have 2–5 times higher risk of postoperative and soft-tissue infections compared to non-diabetics (PubMed, 2019). Around 15–25% of diabetics develop a foot ulcer during their lifetime, and infections are the main reason for hospitalization and amputation in these patients (WHO, 2023).

Routine monitoring and timely treatment can prevent most of these complications.

Key Risk Factors of Diabetes

Age & Life-stage

With increasing age, the risk of developing T2DM rises. One review states: “A strong family history of diabetes mellitus, age, obesity, and physical inactivity identify those individuals at highest risk.” (PubMed)

Although age alone may not be entirely independent of other factors (such as weight, insulin resistance), it remains a widely recognized risk marker (PMC).

Think of age as a “background risk” — as we get older, our pancreatic β-cells may decline and insulin resistance may accumulate.

Genetic & Family History

If you have close relatives with T2DM, your risk goes up. Genetic predisposition and family history are well documented: “Diet, lifestyle, and genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes … T2DM is caused by both environmental and genetic factors” (PMC).

One study: individuals with a higher genetic-risk score for T2DM had increased mortality risk, especially when combined with obesity (PMC).

You can’t change your genes, but knowing your family history helps you act earlier.

Overweight / Obesity (especially central/abdominal)

Excess body fat — particularly around the abdomen — is among the most important modifiable risks. According to a recent resource, “Excess body weight significantly increases the lifetime risk of T2D, from 7% to 70% in men … as BMI increases.” (NCBI)

Another study concluded: “Obesity increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by at least 6 times, regardless of genetic predisposition” (diabetologia-journal.org).

Extra fat, especially around your belly, can make your cells resist insulin (the hormone that lowers blood sugar), boosting the chance of diabetes.

Physical Inactivity & Sedentary Lifestyle

Sitting too much or not doing enough exercise increases diabetes risk. A study summarised: “Among various risk factors … physical inactivity (PA), sedentary behaviors (SB) … have attracted special attention” (Frontiers).

And another: “Unhealthy dietary habits, sedentary lifestyle, and decreased physical activity are closely associated with increased T2DM risk” (BioMed Central).

When you move less, your body becomes less responsive to insulin — so blood sugar stays higher for longer.

What you eat matters a lot. Diets high in refined carbs, sugary drinks, processed foods, saturated fats, and low in fiber/whole grains are linked to a higher risk. From a review: “diet is considered as a modifiable risk factor … a low-fiber diet with a high glycaemic index is positively associated with a higher risk of T2DM” (PMC).

Eating lots of sugar, white bread/rice, and processed fats — and not enough fiber (fruits, veggies, whole grains) — can set the stage for diabetes.

Central/Abdominal Fat Distribution

Though kind of part of “obesity”, the location of fat matters: fat around the belly (visceral fat) is more harmful than fat elsewhere. The systematic review of 106 papers pointed out: “The association between central obesity is also found to be significant for the prevalence of type 2 diabetes” (PMC).

Even if your weight seems okay, a larger waist circumference can raise risk, so waist size can be as important as weight.

Hypertension, Dyslipidemia & Metabolic Syndrome Elements

High blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol/triglyceride levels, and metabolic syndrome are all part of the risk cluster. One review: “dyslipidemia, hypertension … strongly associated with the development of type 2 diabetes” (PMC).

When your blood pressure or cholesterol is off, your risk of diabetes rises — they often share the same root cause of insulin resistance.

Ethnicity & Race

Certain ethnic groups have a heightened risk for T2DM due to genetic, cultural, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors. One source: “Ethnicity strongly associates with the development of type 2 diabetes” (PMC).

If you come from a population with higher diabetes rates (e.g., South Asian, African, Pacific Islander), your risk may be higher — making healthy habits even more important.

History of Gestational Diabetes & Maternal Diabetes

Women who had diabetes during pregnancy (gestational diabetes) are at a higher risk of later T2DM; their children may also have an elevated risk. According to a general risk-factor list: “gestational diabetes … affects about 2–5% of women … those women … face greater later-life risks of developing type 2 diabetes” (diabetes.co.uk).

Having had diabetes during pregnancy is a warning sign — for both mother and child — that future diabetes is more likely.

Sleep Quality & Quantity / Sleep Disorders

Poor sleep (too little, too much, or disrupted) and conditions like obstructive sleep apnoea are increasingly recognised risk factors. The review of 106 papers found: “sleep quantity/quality … are found to be strongly associated with the development of type 2 diabetes” (PMC).

Bad sleep can mess up how your body handles insulin and sugar — so good sleep is a part of diabetes prevention.

Smoking, Alcohol, Psychosocial Stress & Other Lifestyle Factors

Lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and heavy alcohol use, as well as chronic stress, can raise diabetes risk. In the systematic review, “smoking is also found to be a significant risk factor … both active and passive smokers are at higher risk” (PMC).

An umbrella review also mentions stress, micronutrient deficiencies, and environmental exposures (jphe.amegroups.org).

Smoking, heavy drinking, and persistent stress make everything worse: they raise inflammation, insulin resistance, and therefore diabetes risk.

Early Life & Other Emerging Risk Factors

Early-life under-nutrition, low birth weight, childhood malnutrition, exposure to pollutants, and epigenetic changes are emerging as important. A review noted: “Major risk factors include genetics, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, diet, smoking, gestational diabetes, micronutrient deficiencies, and stress” (jphe.amegroups.org).

What happens in early life — malnutrition, growth problems, even poor maternal health — can set the stage for diabetes decades later.

Prevention & Care of Diabetes

1. Early screening & risk assessment

- Screening for pre-diabetes/diabetes is recommended in adults aged 35-70 who are overweight or obese (USPSTF)

- Identifying risk early allows referral to proven prevention programs (CDC).

- WHO emphasizes: “A healthy diet, regular physical activity, maintaining a normal body weight, and avoiding tobacco use are ways to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes” (World Health Organization).

2. Maintain healthy body weight & reduce fat (especially abdominal)

- Weight loss of about 5-7% of body weight significantly reduces progression from pre-diabetes to T2DM.

- Every kilogram of weight loss in one study was linked to a ~16% risk reduction for diabetes (PMC).

- Focus on reducing visceral (abdominal) fat: this improves insulin sensitivity (PMC).

3. Healthy diet (balanced, whole food)

- Eating more whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes and less refined carbs/sugars helps (The Nutrition Source).

- Avoid high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, refined flour, saturated and trans-fats (Health.gov).

- Example: The US CDC’s guide encourages practical eating changes (healthy lunch, snack prep) to make healthy choices easier (CDC).

4. Regular physical activity & avoid sedentary behavior

- Aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (e.g., brisk walking) plus strength/resistance training (Diabetes Journal).

- Break up long sitting periods: it improves insulin sensitivity (Diabetes Journals).

5. Avoid tobacco and limit alcohol; manage other lifestyle factors

- Smoking and heavy alcohol consumption contribute to insulin resistance and increased risk. (While not all sources list alcohol in detail for prevention, the general risk-factor literature supports these.)

- Good sleep quality, stress reduction, and avoidance of persistent high psychosocial stress help too (American Diabetes Association).

6. Join a structured lifestyle-change program if you have pre-diabetes

- The National Diabetes Prevention Program (US CDC-led) has shown that such programs can reduce T2DM risk by more than half (CDC).

- Example: “On Your Way to Preventing Type 2 Diabetes” guide from CDC lays out step-by-step actions (motivation, nutrition plan, habit development) for individuals (CDC).

Care & Management: If You are Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes

Once T2DM is diagnosed, good care means consistent monitoring, lifestyle management, and working with your healthcare team.

1. Work with a multidisciplinary healthcare team

- According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care, management includes not just glucose control but also screening for complications (heart, kidney, eye, foot) and supporting behavior change (American Diabetes Association).

- Self-management education and support (e.g., diabetes self-management education & support, DSMES) helps people learn the skills to manage their condition (CDC).

2. Set realistic glycaemic goals and monitor regularly

- HbA1c (glycated-hemoglobin) is commonly used; targets vary depending on age, comorbidities, and individualized goals. (See ADA standards) (American Diabetes Association).

- In addition to A1c, regular monitoring of blood glucose, foot checks, eye exams, kidney tests, and cardiovascular risk factor monitoring is vital (Wisconsin Department of Health Services).

3. Continue the pillars of lifestyle: diet, exercise, and weight management

- Even after diagnosis, lifestyle changes remain central — healthy diet, regular physical activity, and maintaining or achieving a healthy weight help improve outcomes (American Diabetes Association)

- Nutrition therapy: often working with a dietitian helps. Food choices affect blood sugar, cardiovascular risk, and overall health.

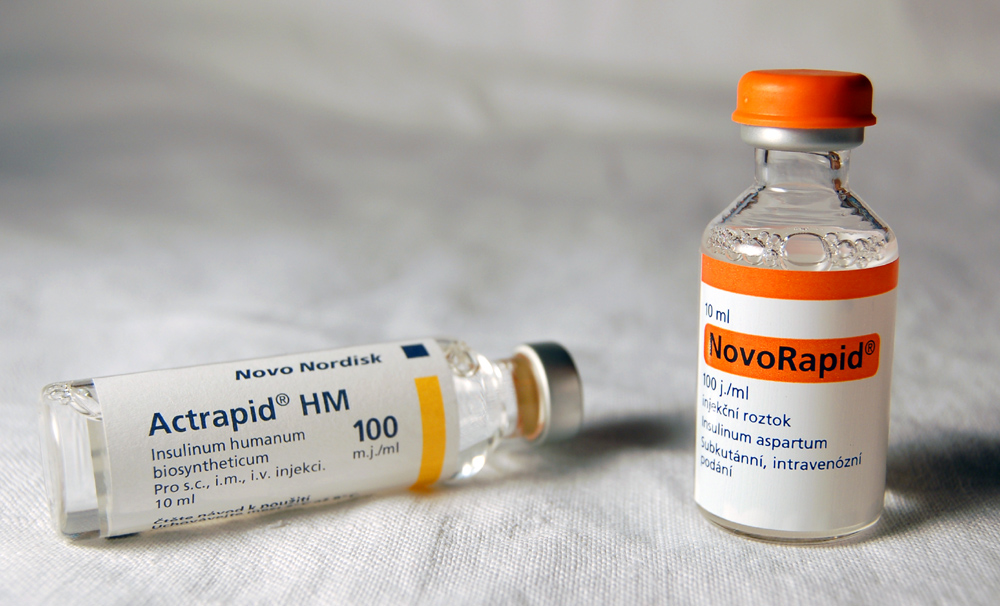

4. Medications & other therapies when needed

- When lifestyle alone isn’t enough to meet glycaemic goals, medications (oral and injectable) are introduced based on individual profiles (kidney function, heart disease, etc). (See ADA standards.) (American Diabetes Association)

- Also, managing other risk factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and smoking is part of complete care.

5. Prevent complications via regular screening & risk factor control

- T2DM increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, kidney disease (nephropathy), eye disease (retinopathy), nerve problems (neuropathy), foot problems, etc. Effective care includes periodic screening for these (Wisconsin Department of Health Services).

- Early detection of complications enables timely treatment and better outcomes.

6. Emphasize long-term behavior change & support

- Sustaining healthy habits is key: regular follow-up, peer support, diabetes education programs, digital tools/telehealth can help (American Diabetes Association).

- Addressing social determinants of health (food security, access to care, health literacy) improves outcomes (American Diabetes Association).

Final Thoughts

Diabetes is not just a medical condition — it’s a global public health challenge. Awareness, timely screening, and healthy living can dramatically reduce its burden.

Let’s make diabetes prevention a daily habit — because small lifestyle changes today can prevent lifelong complications tomorrow.